Suffering and Pain

Suffering and pain are topics that have fascinated artists and their audiences from the Middle Ages to modernity. Appraised from a variety of perspectives, they often expose injustices or else point to moments of extreme personal tension, eliding the distance between viewer and viewed by triggering outpourings of identification and empathy.

As aspects of the judicial process, suffering and pain serve both as punishments and as mechanisms for rehabilitation, depriving convicts either of their freedom or of life itself. For those who followed in Christ’s footsteps, subjecting themselves to the horrors of martyrdom, the experience of suffering and pain offered a formula for emulating his example while establishing models of exemplary devotion. Comparable sentiments are offered by treatments of old age and infirmity, which explore the importance of approaching death with grace and dignity, as well as studies of asceticism, where procedures of self-inflicted suffering enable individuals to overcome the temptations of the flesh or atone for the sins of the past.

A topic of particular importance is the suffering and pain caused by sexual guilt, which can produce some of the most extreme and self-destructive behaviours. A common denominator in each instance concerns how experiences that are personal and intransmissible can be captured in visual form and thereby made real for audiences.

Interior of a Prison

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, c. 1793–94.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

Read the commentaryCrucifixion

The Durham Master, Early sixteenth century.

The Galilee Chapel, Durham Cathedral.

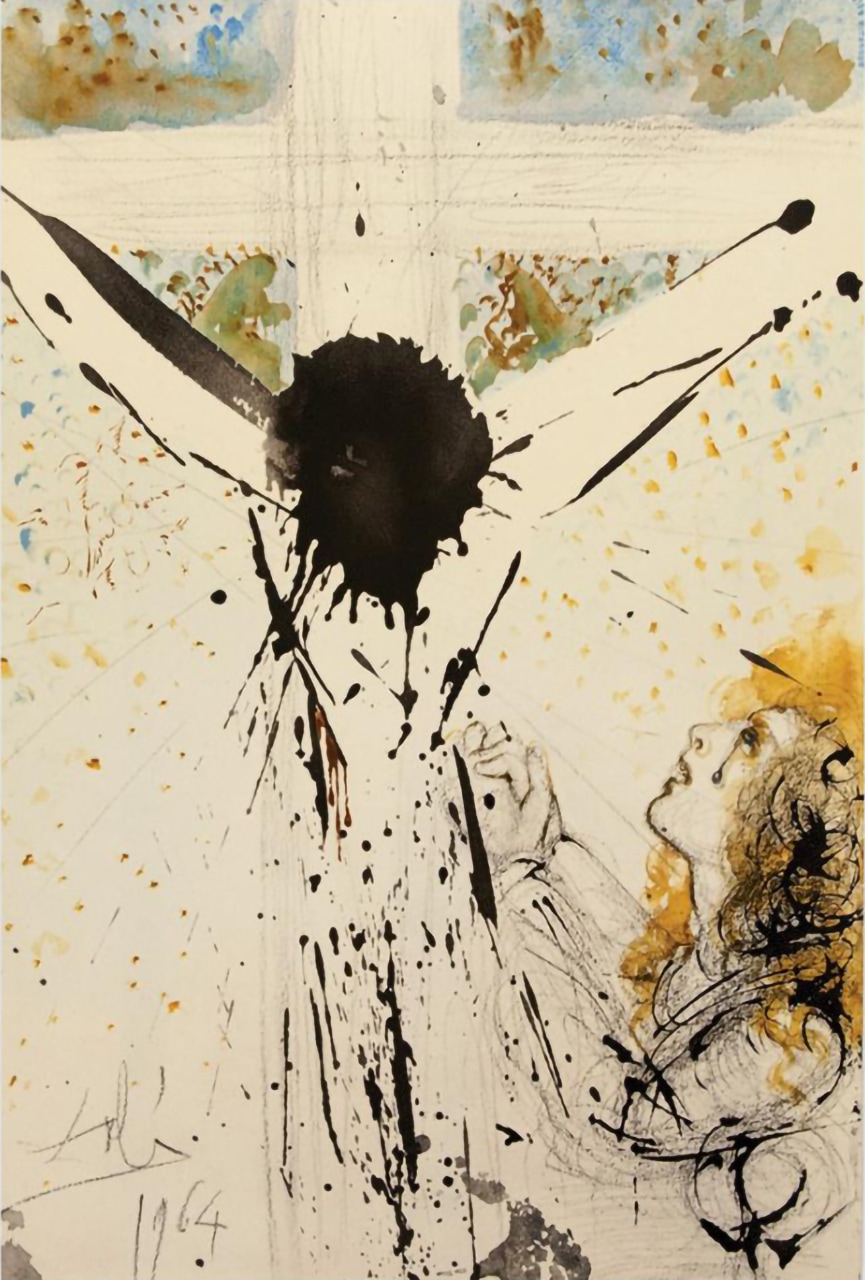

Read the commentaryTolle, tolle, crucifige eum

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1967–69.

St John’s College, Durham University.

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2022.

Read the commentarySt Bartholomew

Unknown artist active in Granada, Late seventeenth century.

University College, Durham University, 18.1214.

Produced in Granada, these two large-scale artworks offer representations of St Bartholomew in his glorious post-resurrection state. Having been flayed alive for preaching the word of God, the saint is characterized as an authoritative and imposing figure, with elegant robes and a full beard flecked with tinges of grey. The knife in Bartholomew’s right hand (unfortunately destroyed in Gaviria’s sculpture) offers a reference to the uniquely harrowing nature of his martyrdom, while the book in his left alludes both to his activity as a preacher and to the concomitant transformation of skin into properties such as leather and parchment, the materials from which books are made.

Read the commentarySt Bartholomew

Bernabé de Gaviria, 1600-1622.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

The Martyrdom of St Andrew

Luis Tristán de Escamilla, c. 1616–24.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

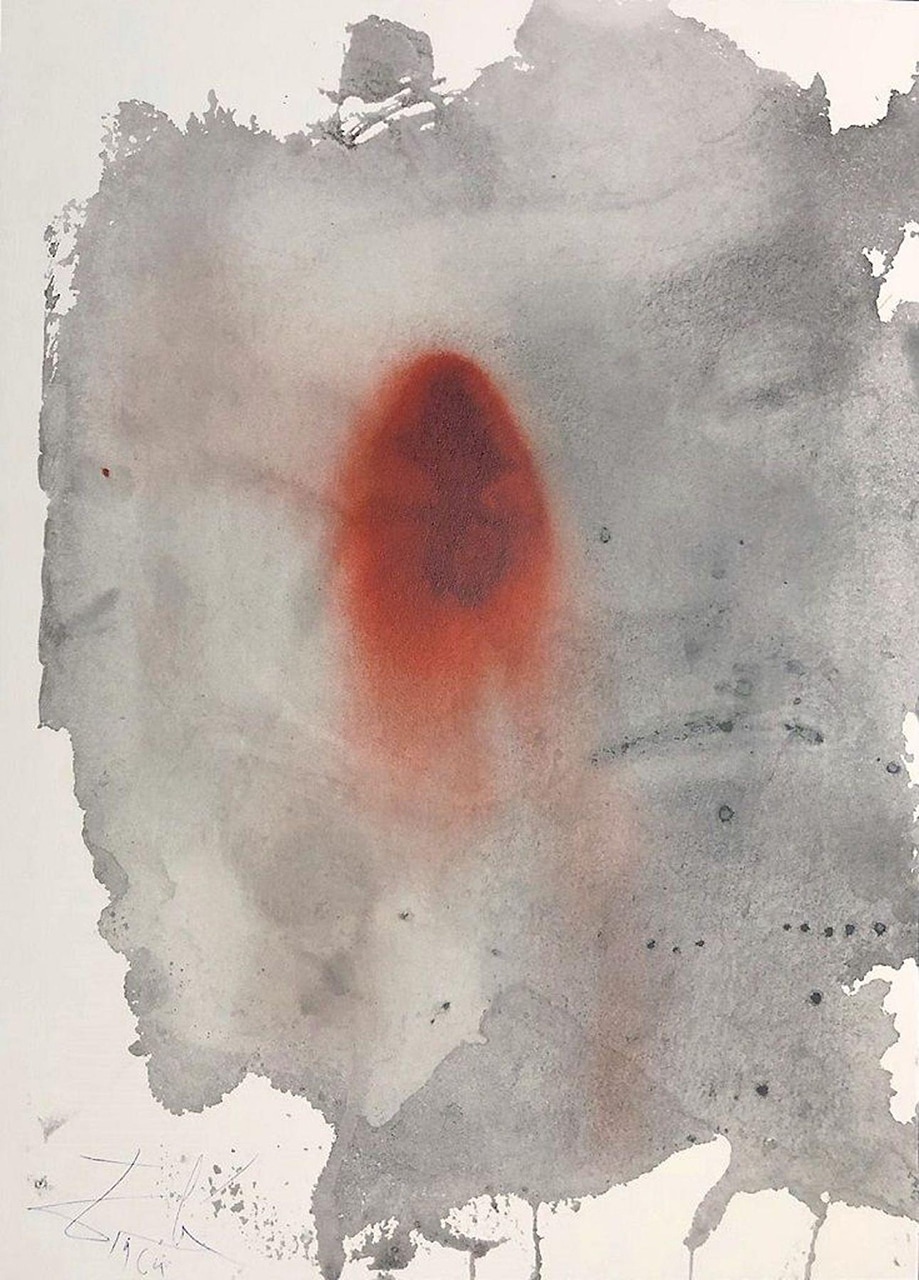

Read the commentaryEgo sum vermis et non homo

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1964.

St John’s College, Durham University.

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2022.

Read the commentarySt Jerome

Antonio de Puga, 1636 (dated).

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

Read the commentaryThe Penitent Magdalene

Mateo Cerezo, c. 1665–66.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

These two painted treatments of Mary Magdalene offer insights into questions of sexual guilt and how suffering and pain are embraced in the Christian tradition as mechanisms for self-improvement. Having spent her life as a harlot, Mary recognizes the error of her ways and repents. In the first painting, by Maíno, she is depicted at a point of emerging self-awareness, while in the second, by Cerezo, her tear-stained face emphasizes the extent of her guilt and the importance of contrition.

Read the commentaryThe Penitent Magdalene

Fray Juan Bautista Maíno, c. 1609.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Two Girls Playing in a Vineyard with a Small Dog

Pedro Núñez de Villavicencio, c. 1670.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Read the commentary